Writing

A look at Studio AATOAA’s piece produced in 2015, a category-dodging visual journey that slips deftly between interactive film, video game and VR experience, yet paves a way forward upon the playable arts landscape. This review was written in 2015 as part of my work in interactive storytelling at UC Santa Cruz.

A moment from “Way To Go”, an interactive piece by Studio AATOA, funded by the National Film Board of Canada

“Yes, you are on your way. It is not your first journey but Way To Go is the next journey before you. A walk through strange country—strange, familiar, remembered, forgotten. It is a restless panorama, a disappearing path, a game, a feeling. Way To Go is a small experience that gets bigger as you uncover it.”[1]

In describing the work, it’s difficult not to see these words as a prescient metaphor for its own journey upon the new media art landscape. Way To Go has been widely reviewed, and a glance at the list of reviewers—Kotaku, Cartoon Brew, Animal New York, The LA Times, The Verge, and Kill Screen Daily—indicates the shifting terrain upon which the work gets placed. It has been characterized as an “interactive animation”, an “interactive film”, a “digital experience”, a “video game”, a “virtual reality experience” and a form of “non-linear interactive storytelling”. At its point of consistency, it is about a journey; about a distinct path and direction. Where uncertainty lies is in which media landscape its path is on.

In describing the work, it’s difficult not to see these words as a prescient metaphor for its own journey upon the new media art landscape. Way To Go has been widely reviewed, and a glance at the list of reviewers—Kotaku, Cartoon Brew, Animal New York, The LA Times, The Verge, and Kill Screen Daily—indicates the shifting terrain upon which the work gets placed. It has been characterized as an “interactive animation”, an “interactive film”, a “digital experience”, a “video game”, a “virtual reality experience” and a form of “non-linear interactive storytelling”. At its point of consistency, it is about a journey; about a distinct path and direction. Where uncertainty lies is in which media landscape its path is on.

Way To Go is physically located—if such a thing can be said of a virtual piece—on the website of its primary funder, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), in the interactive section. The NFB’s mission has evolved since its inception in 1939, and its establishment of the National Film Act in 1950, to expand its film-centric mandate and acknowledge changing practices in both content creation and distribution. Historically the NFB’s prestige has come from exerting a pioneering spirit through the traditional mediums of film, documentary, and animation.

In animation alone, new techniques and technologies have served as precursors to the flourish of the digital age, and have pressed against the edges of conventions and aesthetics in visual and experimental storytelling; for the NFB these include the pixilation animation of Norm McLaren’s anti-war documentary “Neighbours” (1952), interpolation techniques in the computer animation of Peter Foldes’ “Hunger” (1974), and pinscreen animation of Jacques Drouin’s “Mindscape” (1976). But the transition to digital was slow to come. Tom Perlmutter, the NFB commissioner from 2007 to 2013, was largely responsible for ignoring the institution’s philosophical and financial reluctance, dragging it squarely, and insightfully, towards the future. As he noted, “Change. It’s scary. But when things evolve and paradigms shift, we get a chance to try new things, to meet new people, to go to new places”[2].

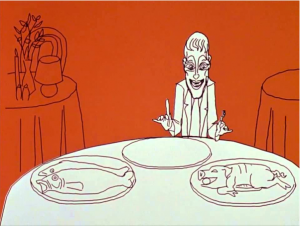

Peter Foldes’ “Hunger” (1974) for the NFB

Jacques Drouin’s “Mindscape” (1976) for the NFB

Way To Go’s existence is the result of a symbiotic relationship with its patron, and in turn the Canadian government at large that funds the NFB. With its traces of animation and documentary-style footage seamlessly commingled and brought to life as an interactive experience, the piece exemplifies the NFB’s historical trajectory, and equally embodies and promotes its ongoing mission. In 2013 the NFB launched a new strategic plan called “Imagine, Engage, Transform; A Vision; A Plan; A Manifesto” solidifying in words the modern steps being taken along a well-trodden path: the “nationalistic mandate to unite Canadians by telling them about each other” [3] while simultaneously drawing global attention and brand recognition to its “innovation and leadership” [4] in film and interactive media. The strategic plan embraces transmedia as a platform for Canadian seeds to be sown, both physically and virtually, so that the “innovative and distinctive audiovisual works and immersive experiences” that it produces “find their place in classrooms, communities, and cinemas, and on all the platforms where audiences watch, exchange and network around creative content.” [5] Across this giant vista of the Canadian government’s initiatives, Way To Go is one of many trailblazing steps in new media art, unconcerned with the exact shape of its footprint as long as its movement is forward.

“BLA BLA” from Studio AATOAA for the NFB

Vincent Morisset and his collaborators previously developed another participatory experience for the NFB entitled “BLA BLA: A Film for Computer.” In the context of this, and other projects by AATOAA, a film lineage emerges more clearly. The award-winning Montreal-based studio states it is dedicated to original digital productions and is “renowned for groundbreaking experiences that merge film grammar and interactivity” [6]. Morisset has made traditional documentary films—“traditional” used here in the new-media-negating sense of sans interaction—but he is more often characterized as an interactive filmmaker. In his works, film, video, documentary and animation sequences are a construct through which interaction provides a kind of subjective independence—an orchestrated freedom to encounter new delineations. The technology is conspicuous insofar as it employs commonly used devices and interfaces to do uncommon things. In Reflektor, participants use the angle and location of their phone in front of the computer screen with “the visceral feel of a flashlight, or prism or shadow puppet” [7], exposing a schism-like projection between the piece’s real and imaginary worlds.

“Reflektor” by Studio AATOA for the NFB

Interacting with “Reflektor” using a cell phone.

Morisset’s philosophy for new media art might be gleaned from the full titles of his works: “BLA BLA: a film for computer”, “Reflektor: a virtual projection”, “Sprawl2: a dance activated film”. “Way To Go”, on the other hand, includes no claim to what it is [8]. These suggest a creative space that is playfully fluid and a-categorical, freely splicing and mixing media forms and participatory elements. As reviewer descriptions for Way To Go indicate, Morisset and his collaborators stride easily into the virtual worlds of play and games. This fits well with the mission of the NFB, and his work has been welcomed at MoMA, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, and the National Taiwan Museum; and at festivals such as Venice, Rotterdam, SXSW and IDFA. The online version of “BLA BLA” was adapted into a children’s interactive installation for Gaite Lyrique in Paris, and the VR version of Way To Go was shown at the Museum of Moving Image, among other places. Despite such reputable endorsements, this whole interactivity sortie bristles the traditional notions held by many institutions that fund public art, where the vexing terrain called “play and games” is more stuffily known as “but is it art?”

The interactive installation of “BLA BLA”.

Morisset and other digital creators, including an executive producer at the NFB, put forth the “Digital Storytelling Manifesto” [9] in 2013 in direct response to shortsighted recommendations to SODEC [10], a public arts funder in Quebec, that failed to contain “significant mention of digital creation” in considering the future of cinema. In a similar vein to the NFB initiative, the manifesto melds Quebec’s prominent global front with innovation and creativity in digital creation and production, concluding that support for such a cultural industry is therefore a national imperative. Yet key points transcend such politics, arguing on behalf of a larger artistic province:

3. Interactive work is not a derivative of any other form of expression. It is an art form in itself. We must define the practice and support it through a unique process tailored to its needs and character.

4. The industry of interactivity is a cultural industry. Its creators are not service providers. It is only through applied support that a culture of authors will emerge.

5. Producing interactive projects involves prototyping artistic and technological ideas. Code and programming are tools of this expression.

6. It is necessary to create favorable conditions for the emergence of an interactive writing culture.

7. The means of distribution constitute part of the creative act.

8. Digital content has already outgrown the screen. The platform for its curation and distribution has not yet seen the light of day.

The particular obstacles to recognition can be inferred from these points. Yet it’s important to note that SODEC has several channels of funding and do provide financial support for interactive works elsewhere (unfortunately they are still called multimedia). The manifesto’s intent is not to reconfigure these channels. Its arguments are pointed specifically at the cinematic arts community that made the recommendations, urging it to release its deep-rooted principles and confront the bigger, inevitable picture of the digital age we live in. New forms of storytelling are not in the future; they are here, now. While facets of traditional modes of representation are discernible within them, the underlying form is fundamentally, physiologically individual. Through them, the path of storytelling is no longer solely linear; it is multivalent and multidimensional. Integral to interactive writing, or “new writing,” is code and programming [11]. These works breach the confines of the screen, existing both within and without, so to speak. And the audience is adapting to—and embracing—its newfound freedom and purpose.

Way To Go makes the essence of this shift practicably and conceptually tangible. By engaging with the work, bouncing off the remnants of the familiar, and experiencing the tension that emerges between narrative freedom and control, one can begin to distinguish this art form’s individuality. Way To Go confirms that we are indeed moving forward, but not by conventional means or over well-known territory.

Those traces of the familiar have led animation, film, and game sites alike to review Way To Go in the context of their comfort zone, while holding it at arm’s-length like an odd incarnation, an experiment in crossbreeding, or a curious outcrop from the standard form. On the animation website, Cartoon Brew, Amid Amidi attempts to distinguish the space he deems “interactive and non-linear interactive storytelling in animated filmmaking” by bravely dipping a toe into the as-yet-unnamed-ness that converts audience to enactor:

“The distinction I would make between games and interactive films is that in games, buttons are pressed to accomplish a task, whereas in filmic experiences, buttons are pressed purely for the sake of advancing a narrative that provides some kind of aesthetic or auditory satisfaction.” [12]

As an “interactive film” it has gained traction by being adapted for the Oculus Rift VR headset. In January 2015 it premiered at Sundance’s New Frontier program, along with nearly a dozen other VR shorts from established studios and independent filmmakers. The enthusiasm that surrounds new presentation technologies can come at a price for the works they display. Either the work benefits from the quickly growing mass appeal without being dependent on it, or the work’s association with the platform directly impacts the judgment of its merits. Renata Adler wrote in 1980, “Movies seem to invite particularly broad critical discussion: to begin with, alone among the arts, they count as their audience, their art consumer, everyone. Television, in this respect, is clearly not an art but an appliance, through which reviewable material is sometimes played” [13]. In the film world, the Oculus Rift’s reputation comes less from its perception as a mere appliance and more from its connotation as a Trojan horse: in other words, game technology that wields narrative-destroying interactivity.

As an “interactive film” it has gained traction by being adapted for the Oculus Rift VR headset. In January 2015 it premiered at Sundance’s New Frontier program, along with nearly a dozen other VR shorts from established studios and independent filmmakers. The enthusiasm that surrounds new presentation technologies can come at a price for the works they display. Either the work benefits from the quickly growing mass appeal without being dependent on it, or the work’s association with the platform directly impacts the judgment of its merits. Renata Adler wrote in 1980, “Movies seem to invite particularly broad critical discussion: to begin with, alone among the arts, they count as their audience, their art consumer, everyone. Television, in this respect, is clearly not an art but an appliance, through which reviewable material is sometimes played” [13]. In the film world, the Oculus Rift’s reputation comes less from its perception as a mere appliance and more from its connotation as a Trojan horse: in other words, game technology that wields narrative-destroying interactivity.

Yet new forms of storytelling are upon us, and the film industry, whether intrigued by the artistic prospects of new content or enticed by the game industry’s profit margins, believes the future of film integrates game and cinema in the form of immersive virtual worlds. You are “inside what you’re watching” [14]. VR Cinema, as it is called, benefits from the relative ease-of-use of the Oculus Rift—the most basic interaction is to simply turn one’s head, and move one’s body, to take in a full 360-degree view. Still, in “Hollywood looks to bring virtual reality cinema to life”, Steven Zeitchik of the LA Times notes that filmmakers grapple with creating a narrative experience for an audience that behaves like a fidgety kid:

“The thinking is that because people can now look and wander anywhere, they need more guidance, lest they walk right out of the story you’re trying to tell.” [15]

He appreciates that Way To Go is a “straight line [that] guides the viewer through the landscape, limiting meandering” [16]. And while this is true, it’s a distorted perspective, and more of a consequence of the painful and confusing shift from the linear to the nonlinear rather than a sense of the possibilities. It’s a necessary observation nonetheless and the hope is that, as filmmakers evolve, they will come to learn that the user’s gaze and movement are not a step or glance away from the story, they are the fabric of story itself. Mark Serrels at Kotaku may have stumbled upon this notion inadvertently: “It’s very much an “art” game, whatever that means, point being you will not be shooting anything” [17]. If one thinks like a cinematographer, the user will indeed be shooting; in this case, their view of the storyworld. Storytelling is path directing, whatever the means.

Creators of “Way To Go” Vincent Morisset, Philippe Lambert, Caroline Robert, Edouard Lanctót-Benoit

Perhaps not surprisingly, the video game writeups of Way To Go seem to better comprehend the aesthetic aspects of this form of new media art, even if they don’t identify it as such. In the Kill Screen review, Jess Joho writes:

“It’s always funny when creators and/or critics describe a piece of art work as being about, oh you know, just life, time, love, death, and space. Vincent Morisset didn’t describe Way to Go like that, but he should have. Because it really is about life, time, love, death and space—all at the same time. At least, that’s the closest I can come to summarizing it in one sentence.” [18]

Interviews with Morisset readily tease out of his works a strong connection to videogames; they “seemed the best place” to explore the themes of “space and time and control” [19]. As an interactive filmmaker he sees “human beings as a paradox when it comes to experiences: on one side, we want to be taken by the hand; but on the other, there’s the strong desire for freedom and control” [20]. At its core, the world of games understands this tension, which can be more faithfully portrayed as the rules of the system.

Interviews with Morisset readily tease out of his works a strong connection to videogames; they “seemed the best place” to explore the themes of “space and time and control” [19]. As an interactive filmmaker he sees “human beings as a paradox when it comes to experiences: on one side, we want to be taken by the hand; but on the other, there’s the strong desire for freedom and control” [20]. At its core, the world of games understands this tension, which can be more faithfully portrayed as the rules of the system.

Way To Go might fall into the category of a proceduralist game, as described by game designer and critic Ian Bogost, which relies on “computational rules to produce their artistic meaning” [21]. Bogost gives more weight to rules over visual, aural and textual elements in the way an interactive work expresses its idea. And yet these are the very tissue through which the rules are enacted, performed and unraveled; meaning emanates as much from the languages and grammars employed as they shape, metaphorically, what is spoken and heard. Morisset states it is the “the mix of cinematic grammar and videogame controls [that open] this unique emotional window for the spectator” [22]. A window here is an untouchable moment frozen in time, like the space between two frames of animation or the edit between two shots of film, but with a 360-degree space of possibility. The course of action is an intersection between author and user, and in this moment, path-directing—the freedom and control of storytelling—is both collaboration and compromise.

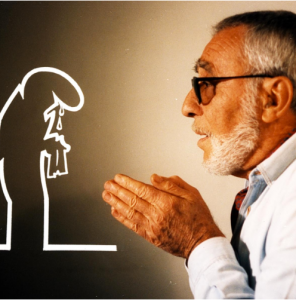

Osvaldo Cavandoli, Italian cartoonist famous for the animated shorts, “La Linea”

Before you begin your journey in Way To Go you are likened to one of several possible explorers—Jean Painleve, Marco Polo, Maria Merian, Alice, Sonic, Osvaldo Cavandoli [23]—hinting at the various art forms (film, documentary, animation, game) that color and represent our actions. Yet the end—the completion—of the path doesn’t evoke a sense of arrival, or of ultimate discovery. It feels more like a vague, future land made of wispy aspirations and unshaped expectations. Rather, it is the path itself that reflects the theme of exploration — how we look at things when we go from one point to another. As it is with many stories, the journey is the destination, and, moreover, the freedom to take your time. At any given moment, your precise location bisects what has been traveled and what lies ahead. Way To Go’s strides upon the new media landscape are not to reveal precisely where we have landed, but to remind us that our steps towards the future are always made in the present. You may move forward with an eye to the past, or pause and reflect on where you have been, but it won’t change the fact that what you have discovered is right now.

[1] “Way To Go” Way To Go, National Film Board of Canada, 2015. Web. 19 Jan. 2015

[2] “How Tom Perlmutter turned the NFB into a global new-media player.” Kate Taylor, The Globe and Mail, n. d. Web. May 2013.

[3] Ibid.

[4] National Film Board of Canada, National Film Board of Canada, 2012. Web. 13 Nov. 2012.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Way To Go” Way To Go, National Film Board of Canada, 2015. Web. 19 Jan. 2015.

[7] Studio AATOAA, Studio AATOAA, 2015. Web. Jan. 2015.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Quebec’s Digital Storytelling Manifesto.” POV Staff, Public Broadcasting Station (PBS), n. d. Web. Nov. 2013

[10] Société de Développement des Entreprises Culturelles (SODEC)

[11] The entire Digital Storytelling Manifesto can be found at: nouvellesecritures.org/index_en.html

[12] “’Way To Go’ Is Unlike Any Other Animated Short You’ve Experienced.” Amid Amidi, Cartoon Brew, n. d. Web. Feb. 2015

[13] “The Perils of Pauline.” Renata Adler, The New York Review of Books, n. d. Web. Aug. 1980

[14] “Sundance 2015: The pleasures and perils of VR Cinema.” Steven Zeitchik, LA Times, n. d. Web. Feb. 2015

[15] “Hollywood looks to bring virtual-reality cinema to life.” Steven Zeitchik, LA Times, n. d. Web. Mar. 2015

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Stop What You’re Doing And Play This Video Game Right Now.” Mark Serrels, Kotaku, n. d. Web. Feb. 2015

[18] “Experience Life And The Elasticity Of Time.” Jess Jho, Killscreen, n. d. Web. Feb. 2015

[19] “Making Way To Go A Psychedelic Walk In The Park.” Michael Rougeau, Animal, n. d. Web. Mar. 2015

[20] Ibid.

[21] Bogost, Ian. How To Do Things With Videogames. Miineapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011. 13. Print.

[22] “Vincent Morisset’s ‘Way To Go’ Gives Interactive Some Feeling.” Staff, SourcEcreative, n. d. Web. Mar. 2015

[23] Jean Painleve was a film director and biologist specializing in underwater fauna; Marco Polo was an explorer and merchant from Venice; Maria Merian was a German-born naturalist and scientific illustrator; Alice refers to the main character in Alice in Wonderland; Sonic refers to Sonic the Hedgehog game character by Sega; Osvaldo Cavandoli was an Italian cartoonist and created of the animated shorts series, La Linea.